Really??!!

Reality and its discontents....

It’s ironic, or maybe just severely human that, in what’s touted as an age of uncertainty, black and white thinking, the epitome of certainty, is so common.

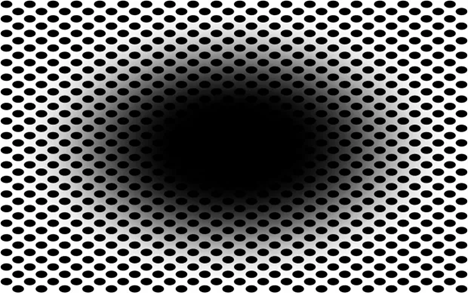

Living in a world of well-defined and exclusionary facts (where fact “A” definitively denies fact “B”) can feel comfortable and secure. But what about this example of black and white seeing:

I promise you that that is a still picture; if you’re in the 86% of us who see the black hole as expanding, you have two apparently mutually exclusive “facts”: the image is not moving vs seeing that damned hole growing. If you take the study (linked via the caption) seriously, then you have a third fact: about 1 in 8 humans only see an unmoving black smudge on a pattern of black ovals on a white background: about 12% of your fellow humans do NOT see what you see: your facts differ

We have had a sprawling sociocultural conflict over the last 60+ years over the relationship between human understanding and reality. At one extreme are the few remaining positivists who hold that human knowledge is direct, if incomplete, knowledge of an ultimately knowable reality and that we (can) know that reality as it actually is.

At the other extreme are the relativist post-modern constructivists who hold that all knowledge is a construction of individuals and their cultures which bears no necessary relationship to any reality and that each knowing is essentially unchallengeable as it is the lived experience of the knower(s).

There are, of course, many shades between these extremes but there is a divide between those for whom (at least some) knowledge is sanctioned by reality and those for whom no preference can be made between ways of knowing and describing the world. With tongue wandering in the direction of cheek, let’s call the former “realists” and the latter “arealists”. My somewhat impatient sympathies lie, with some reservations, with the realists.

Oddly enough, the realists are simply terrible at contesting in the public domain the dominance of arealists, at least in the Anglo-American cultural sphere. The major handicap with which I see the realists hobbling themselves is a terror of granting any validity to a constructivist epistemology. An example, which motivated me to this essay, was an article in Quillette & RealClearPolicy recently, titled, with unknowing irony “The Emptiness of Constructivist Teaching.” There’s a bit of ground to cover before talking about the irony.

The problem that the realists (won’t) face is the history of modern science, particularly the hard sciences and, most particularly, physics. This has seen a series of demonstrations that our models of our world/universe are always partial and contingent. That is, how we know the world changes as we encounter it at different scales and shapes, and for different purposes. For example:

Newtonian mechanics was quite satisfactory until the end of the nineteenth century when our increasing ability to investigate the universe at larger scales made it apparent that not everything complied with Newtonian formulae for calculating (predicting) acceleration and velocity (a = F/m and v = u + at).

Even in the pomp of Newtonian mechanics, James Clerk Maxwell’s equations were the only model for working with electricity, magnetism and optics. Again, as we became able to measure and interact with the world at finer levels of granularity, we found that Maxwellian modelling did not match phenomena which are now more accurately modelled through quantum electrodynamics.

Euclidian geometry is excellent for measuring one’s garden and even city blocks. At that scale, it seems obvious that parallel lines do not meet. Expand one’s scale to a significant fraction of the earth’s surface however, and one realises that there is a set of parallel lines that do indeed meet.

Quantum physics made painfully obvious that, at very small scales,

What one could see depended on how one looked: perform a wave-like experiment and you’ll get wave-like results; perform a particle-like experiment and you’ll get particle like results. (Yes, I know the double-slit work crosses that boundary, sort of).

“Looking” alters the object/system observed

One can never be entirely sure of both location and momentum of a particle.

….

All of these examples are to illustrate that our models, our ways of understanding the world, indeed even understanding the same domain of enquiry within the world, change as our capabilities and interests or purposes change. Many more examples in other fields could be given: geology in general, tectonic plate theory, Darwinian theory (its advent and its development), the multiple theories (some of them more narrative than theory) spawned by psychology, sociology, economics, religion, ….

Each of these models or domains of knowledge allows us to work with different aspects of our world and attempts to explain how those aspects work. Some obviously with greater success than others. We also find that applying the “old” model in new situations or for new purposes often gives unfortunate results. Applying Euclidian geometry rather than spherical geometry when sailing or flying long distances (for example, a trans-oceanic trip) is a beginner’s mistake which, for courses other than due north or south, results in hilariously (or tragically) missed targets. Using Newtonian concepts and relations of mass, space, time and velocity for GPS calculations would disrupt much of our economy and military.

I can see no alternative to understanding our common stock of knowledge as constructed (I actually prefer “developing”) through our encounters with the world at different scales, with different technology and for different purposes. This is the base of a constructively constructivist epistemology.

The arealists, however, don’t rest here. They leap to the conclusion that, because knowledge is constructed and subject to change, that there is no basis for preferring one culture’s knowledge to another and that, by strong implication, there can be no knowable objective reality. An example is the valorisation of Indigenous or First Peoples’ world knowledge as “science” on a par with formal, technologically sophisticated science. As with my examples above, indigenous knowledge is demonstrably excellent for informing decisions by people in the eco-situation of hunter-gatherer or other non-industrial societies. However, in general, it is rarely (NOT never: rarely) useful in defining and solving problems of modern, high population, interdependent, industry dependent societies.

I have to point out, despite the arealists determinedly ignoring this point whenever it’s made, that by their own doctrine, there is no reason to prefer or privilege their ideas. In their position of absolute relativism, it seems to me that they are insisting that we all always take a god’s eye view of human thought, needs and activities. This god’s eye view is the view from the end of time where nothing survives, no purposes continue, all wants are made as nothing.

That can be a useful perspective to counter our self-centredness but we don’t live there. We live here, in the world of effort and consequences arising from that effort. For me, this points to a most apposite criterion for assessing ideas: if we like the actual consequences that flow from effort informed by a worldview or model, then that is a useful model for the specific purposes to which it was applied. “Specific purposes” strongly implies specific people and/or institutions.

What seems to me to be a mature, even wise, approach is that attributed to George Box: “All models are wrong; some models are useful.” I prefer to expand it to “All models are wrong; some models are useful for particular purposes in particular situations.” (N. J. Enfield might, I think, add “in a particular language”).

Both Box’s original and my humble extension are disruptive to (and perhaps even transgressive of) ideologies of all stripes, whether socio-economic, religious/spiritual, psychotherapeutic, political, philosophical, …. They do seem to me however, to provide a constructive way out of the intellectual (and spiritual) cul-de-sac of absolute relativism.